Materials shape civilizations

Rather than looking for brand new materials, material scientists today are focusing on developing existing materials through revolutionary new processes. The results of their work will undoubtedly change the world around us – and possibly help to save it.

The development of new materials is perhaps one of the most important endeavors of humanity, defining historic periods and changing the way the world around us looks. After all, the stone, iron and bronze ages were so named because of the materials that were most in use during those times.

When it comes to thinking about tomorrow’s materials today, the biggest focus is on sustainability. And material science is key to making secure, clean and efficient energy systems possible as well as making a whole range of industries, from transportation to manufacturing, sustainable.

Going into material science is a way to save the world, because you can really have an impact on sustainability.

Annika Borgenstam is professor at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Stockholm’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology. She uses the Eiffel Tower as an example of how material science can lead to a more sustainable world.

“If we used the advanced high-strength steels that we have today, we could build four Eiffel Towers with the same amount of material that was used originally,” she says. “Building lighter constructions will mean that less transportation of material is necessary, and less material needs to be produced. Both factors lead to less CO2 emissions. Stronger steel also means that aircraft and cars and such will weigh less, which means less CO2 emissions.”

Radical restructuring

Material scientists are searching for materials that are lighter and can withstand higher temperatures and more corrosive atmospheres.

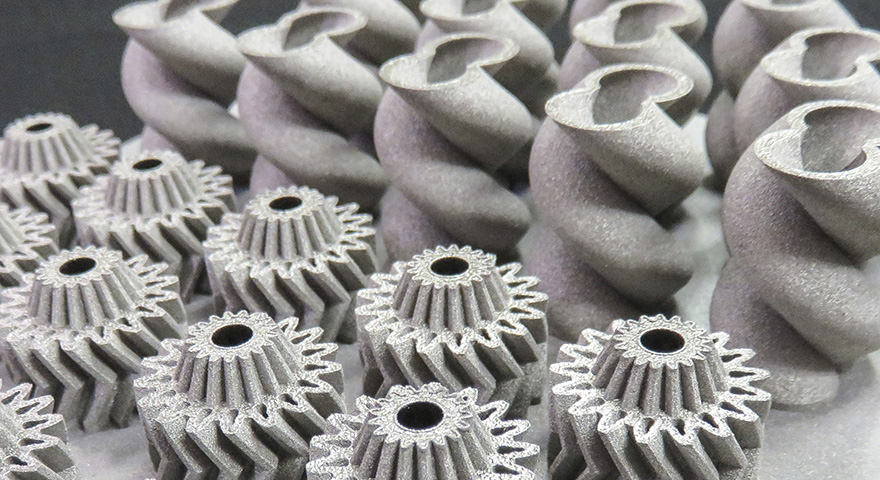

But rather than looking to actually develop brand new materials, today the big push within the industry involves the (often radical) restructuring of existing materials, using revolutionary new processes such as additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, and computational modeling.

“Additive manufacturing will open up completely new ways of using the same types of materials that we have today, by building in the properties that we need,” says Borgenstam.

Additive manufacturing has opened up completely new ways of using the same types of materials that we have today, by building in certain properties and allowing products to be topologically optimized.

Additive manufacturing has opened up completely new ways of using the same types of materials that we have today, by building in certain properties and allowing products to be topologically optimized.

One of the reasons why the focus in materials science is now on new processes and the development of existing materials is because the development of brand new materials can take many years. And while there is a push to replace certain scarce materials such as cobalt, which is used in cutting tools and electric car batteries, material scientists are also increasingly focusing on recycling materials.

Difficult to compete with steel

Borgenstam cites steel as an example of an existing material for which there is no need to find a replacement. “Steel is fully recyclable, cheap and abundant, and we can produce it with a large spectrum of different properties,” she says. “It is difficult to compete with that. There is still room for improvement with steel. We are far from reaching its theoretical strength.”

Perhaps one of the biggest issues facing the development of new materials is a shortage of young people with the right competencies to undertake the relevant research. “It is not that easy to recruit young people into materials,” says Borgenstam. “It is not as well known, as physics and chemistry are, and aspects of it, like the steel industry, are sometimes presented negatively in the media.”

But, she adds, this is an area in which young scientists and engineers can have a huge impact on the world around them. “I would advise young people that going into material science is a way to save the world, because you can really have an impact on sustainability and saving the environment. There are so many positive effects from using better materials, and we need to show them that.”